Despite being the most digitally connected generation, many young Canadians are disconnecting from politics, and one political scientist warns that democracy could suffer for it.

Paul Howe, author of Citizens Adrift: The Democratic Disengagement of Young Canadians, said in an interview that youth disengagement has become a long-term shift, not just a phase, and one that poses serious risks to the country’s democratic health.

“Youth political disengagement has gone from being a marginal concern to a core threat,” Howe said. “Without meaningful participation, democracy becomes brittle.”

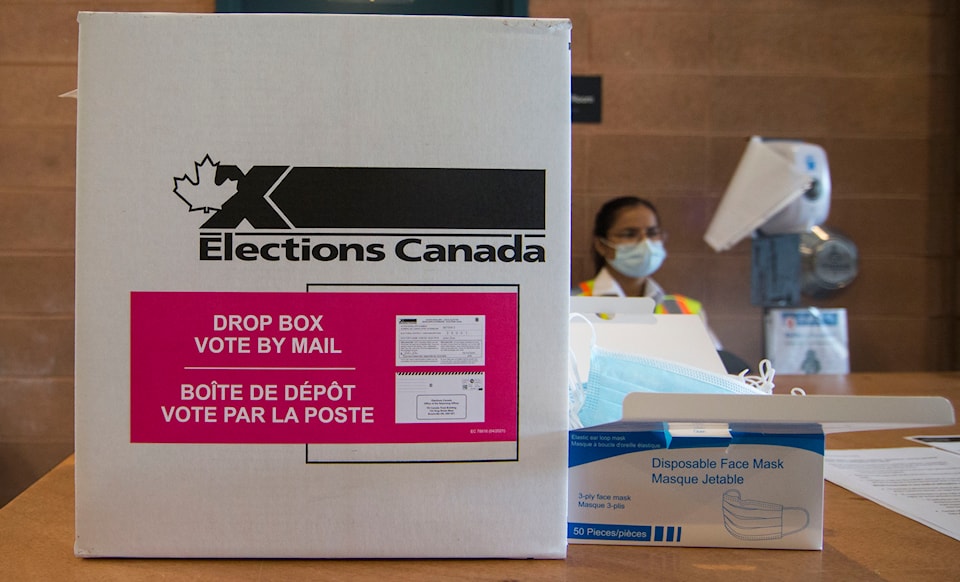

According to Elections Canada, voter turnout among Canadians aged 18 to 24 dropped to 46.7 per cent in the 2021 federal election, a significant decline from 57.1 per cent in 2015 and 53.9 per cent in 2019.

But Howe says voting is only one part of the problem.

“The data show a long-term decline in civic literacy and engagement,” he said. “It’s not just about showing up at the polls. It’s about understanding how the system works and believing your voice matters.”

At Humber Polytechnic’s North campus, that disconnect is already being felt.

“I didn’t vote in the last election because none of it felt real to me,” said second-year media studies student Hannah Chen. “All the parties seemed the same, and no one was really talking about students or people my age.”

Howe believes a lack of meaningful civic education is a major contributor to this disinterest. Many young people, he said, leave school without understanding how government decisions affect their daily lives, or how to influence those decisions.

“Civic knowledge doesn’t just happen,” he said. “It has to be taught, reinforced and connected to people’s lived experiences.”

First-year business student Marcus Ajayi agrees.

“We had one civics class in high school, and it was boring and confusing,” he said. “Now that I’m older, I care more about stuff like rent and jobs, but I still don’t really know how to get involved or who’s responsible for what.”

Howe also points to the growing influence of online spaces, where misinformation and political cynicism are common. He says that can reinforce the idea that politics is distant, corrupt or irrelevant.

“Young people don’t see themselves reflected in politics,” he said. “And when they do try to pay attention, they’re often met with negativity or complexity that pushes them away.”

He warns this sense of exclusion leads to a vicious cycle, one where the needs of young Canadians are overlooked by policymakers, leading to more disengagement and frustration.

“The fewer young people who participate, the more their voices are ignored, and the more disconnected they feel,” Howe said.

Programs like Student Vote Canada are trying to address this gap. Run by CIVIX, a non-partisan civic education charity, the program gives students under the voting age a chance to take part in mock elections that mirror actual ones.

In 2021, more than 800,000 students participated, learning about democracy through real-world experience.

The decline of civic engagement is also being studied in relation to the collapse of local news. A 2018 study in the Newspaper Research Journal reported that the U.S. lost more than 1,800 print newspapers between 2004 and 2015 due to closures and mergers. As local papers vanish, so does the information citizens rely on to stay politically informed.

Several studies suggest that communities with diminished local news see lower voter turnout, weaker civic knowledge and reduced political accountability.

One working paper, titled Financing Dies in Darkness? found that U.S. municipalities experienced increased borrowing costs and government inefficiency following newspaper closures, evidence that the absence of watchdog journalism affects governance itself. Other research links reduced local political coverage to falling voter participation and lower awareness of candidates or issues.

In one study of U.S. House campaigns, areas with less press coverage saw a decline in citizens’ ability to evaluate political choices or even name the parties involved. While these are U.S.-based studies, the implications for Canada are relevant. As local media outlets here face similar pressures, scholars and observers worry about the ripple effect on democratic engagement, especially among young people already tuned out from the political process.

“We need to make politics accessible and relevant,” Howe said. “That starts in schools, but it also means political leaders need to do a better job connecting with young people and restoring trust.”

Despite the discouraging trend, Howe remains cautiously hopeful. With sustained efforts in education and outreach, he believes the democratic gap can be closed.

“Democracy is not self-sustaining,” he said. “It depends on active, informed citizens, and we need to start cultivating them now.”